Gardens of the South African Cape

November 2016

A ten day tour of Cape Town and the South African winelands, organised by Angela Durnford of MGS Italy, including botanical walks and visits to 23 wonderful gardens.

Click on the tabs below to read reports on different aspects of the trip.

Click on the images to enlarge them

Gardens of the Stellenbosch Winelands

Around an hour’s drive east of Cape Town are the winelands of Stellenbosch and Franschhoek. This was the starting point for our ten day tour of the gardens of the South African Cape, wonderfully organised by Angela Durnford, head of MGS Italy. Angela has a close affinity with South Africa and has a home in Cape Town, so we were lucky to have an insider’s knowledge of this very different part of the world.

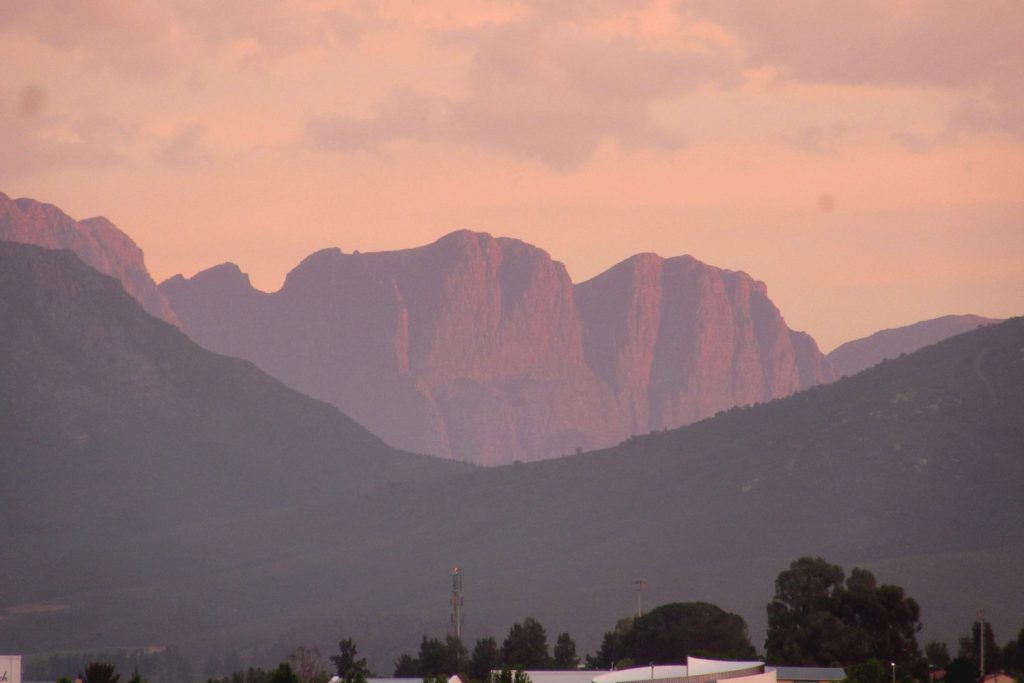

Our first base was the wine estate of Kleine Zalze, just south of Stellenbosch. From the balcony of our room the views of the surrounding mountains were magnificent, ever present and continually changing, especially at sundown. Later we realised that mountains would define or encircle every garden we would visit on the tour.

Vergelegen

The Vergelegen (pronounced ‘verhelehen’ and meaning ‘situated far away’) Estate in Somerset West, to the south of Stellenbosch, was founded in 1700. Set against a backdrop of the Hottentots Holland mountains, it was the perfect introduction to Cape Dutch architecture, heritage and gardening.

We learned about how the early homesteads were all single storey, with the small upstairs space being used for storage. Restio techtorum, the cape reed, was used for thatching.

In the surrounding garden the early settlers planted camphor trees, Cinnamon camphora, natives of China and Japan but introduced to the Cape in about 1670 via the Dutch East Indies. At much the same time, Dutch settlers planted the first specimens of Quercus robur, the English oak.

We were able to admire what is believed to be the oldest living oak in South Africa, planted between 1700 and 1706 by Willem Adriaan van der Stel. A younger, but much venerated oak, was planted in 1928 from one of the last acorns of King Alfred’s oak at Blenheim Palace in England.

The gardens close to the house are formal and include a herb garden with beautifully clipped hedges and a rose garden mulched with apricot kernels.

Further away are lawns with more wonderful trees:

Calodendrum capense, the Cape horse chestnut

Erythrina lysistemon, with stunning red flowers

Morus alba, the white mulberry, another Chinese import, grown as a source of food for silkworms

Stellenbosch University Botanical Garden

This garden is located in the historical centre of Stellenbosch and is the oldest university botanical garden in South Africa

Mature trees and shrubs of all types are densely packed together and interspersed with broad walkways and narrow shady paths.

Interesting plants:

Turnbury, a garden In Devon Valley

Sue’s garden in Devon Valley is surrounded by a small vineyard which produces 1800 bottles of Merlot each year. The garden was started seven years ago and is constantly evolving.

The rose garden in front of the house only looked good for a short time each year, so the roses were dug up and re-planted in the cutting garden at the back. The front was then re-planted with Mediterranean shrubs, which are clipped in Provençal style.

The banks of a stream have been planted with indigenous plants and there is a vegetable garden, a long herbaceous border, a shade garden and a collection of camellias.

Paradyskloof – the Dylan Lewis Sculpture Garden

For the past seven years, artist Dylan Lewis has been creating a 7-hectare sculpture garden around his studio in the foothills of the Stellenbosch Mountains. Here, cultivated farmland gives way to a rocky wilderness where leopards still range. Dylan sculpted the land with a bulldozer to create mounds and hollows – the concept being that the curvaceous ‘female’ mounds would contrast with the rugged ‘male’ mountain landscape beyond.

A lake sits in a hollow, backed by a poplar grove. The mounds are planted with carefully clipped evergreens, their shapes created by the artist. Trees are carefully chosen and their canopies lifted so each is a work of art. Into this landscape seventy-five of Dylan’s sculptures have been placed, almost all cast in bronze.

The hard-landscaping materials have been beautifully chosen. Walls, and a circular studio, have been built out of rounded, golden pebbles.

At the far end of the lake, a narrow gully has been artfully cut into rosy stone to act as an overflow channel.

The plants have been chosen by horticulturalist Fiona Powrie, who was the guide for our visit. Around the studio, Dylan wanted clipped evergreen hedges which would tone well with the olive-coloured foliage of the trees.

Further away, the mounds have been planted with indigenous shrubs to echo the colours of the fynbos beyond. Plants on the mounds include Coleonema pulchellum, Pelargonium botulinum and some low growing proteas and ericas.

Near the stream are drifts of restios, then as the land rises, the coral-red, winged fruits of the hopbush, Dodonaea viscosa add a hint of colour.

This colour is echoed elsewhere in the garden with the rusty red flowers of the aromatic shrub, Salvia lanceolata and the dark pink flowers of the Ruby Grass, Melinis nerviglumis.

Statues, mainly of animals, have pride of place, some tucked into the foliage, others taking centre stage. This is an awe-inspiring amphitheatre of nature, garden and art.

The Old Nectar Gardens

Set amongst the sandstone mountain ranges of the Jonkershoek valley and amongst 200-year old oak trees, the gardens at Old Nectar are the creation of Una van der Spuy, the doyenne of South African gardening and author of 20 books on horticultural topics. Una created the gardens during the 71 years that Old Nectar was her home, from 1941 until her death in 2012, aged almost 100.

We were welcomed by her son, Peter, who has taken over care and development of the two-hectare site.

The approach was along a driveway, then under a pergola with brick pillars, up which grew roses and a stunning deep pink Phaedranthus buccinatorius.

In turn this led to a rose garden, then along a magnolia walk and through borders of flowering shrubs to the garden in front of the classic Cape Dutch homestead, originally established in the early 1700s and re-built in 1815.

Everywhere was a profusion of plants and of colours. We particularly admired a tall but slender tree covered in sweet-smelling yellow to orange flowers and were told that it was a Hymenosporum flavum, native to eastern Australia, where it is known as the native frangipani.

We made our way to the terrace in front of the house, then entered through the central hallway. Here Peter explained that an indigenous hardwood Podocarpus longifolia, known locally as yellowwood, had been used for the interiors.

From here we went on to the new gardens on steep banks behind the house which are being laid out with indigenous plants including restios and helichrysum.

Finally, after refreshments including a sticky, sweet, local delicacy called ’Koeksisters’ we posed for a group photo on the steps.

Babylonstoren

Babylonstoren is a well-preserved Cape Dutch farm, with buildings dating back to the 1750s. Ten years ago the owners decided to develop it as a hotel, with a restaurant, farm shop and garden. All the 300 varieties of plant grown here are either edible or have medicinal value.

The majority of the produce goes to the restaurant or is sold in the shop. 160 people work on the estate, many of them living in the 28 workers’ houses. There are also 16 houses for rent.

The 3.5 hectare garden was designed by French architect Patrice Taravella on classical principles. It has a geometric layout and is divided into sections for stone fruits, citrus, berry fruits, vegetables and indigenous plants.

When the land was being rotivated ready for planting, many fragments of pottery were dug up, both Dutch delft and Chinese.

Our guide led us along the straight paths between the sections, sometimes beneath shade-providing pergolas, sometimes under a very hot sun.

Many of the junctions are marked by a pyramid-topped square pergola up which a climbing rose had been trained. Paths are lined by clipped hedges or by espaliered fruit trees.

Our attention was drawn to the edible properties of the plants we passed:

Portulacaria afra (used in salads)

Carissa macrocarpa (also known as the Natal plum)

The section dedicated to South African plants was small, because, interestingly, very few of the huge number of indigenous plants are edible. A notable exception is Citrullus lanatus var. lanatus, the watermelon, which is thought to have originated in South Africa. This part of the garden featured four Schotia brachypetala trees which are grown for their beautiful red flowers which produce copious amounts of nectar, and for their edible seeds.

We were also surprised to see Carpobrotus edulis (the Hottentot fig, or ice plant) and C. acinaciformis (the sour fig) being grown as ground cover and for their edible fruits. Most Carpobrotus species are invasive in California, in Australia and on coastal areas of the Mediterranean, but in their native country they seem not to spread.

We wandered towards the restaurant, for a delicious lunch made from vegetables and fruits grown in the garden.

On the way, we came across rather striking bird boxes on poles and an interesting garden seat, which Sandra was keen to try out…

Schoongezicht and Rustenberg

Schoongezicht and Rustenberg are adjacent properties in the Idas valley with 880 hectares of land used for vines, farming and as a habitat for indigenous flora and fauna. Each property has an extensive garden cared for by the owner and by head gardener, Pietman Diener.

The Schoongezicht garden includes an ornamental lily pond (reminiscent of the Russell Page one at St Jacques de Couloubrier), a garden of perfectly clipped box topiary and a 200 year old pergola.

The planting style is English, and includes roses, foxgloves, salvias, agapanthus, sedum, anemones and day lilies.

However, for many of us, the highlight was the intricate labyrinth, constructed of brick and river stone to exactly the same design as the 13th century original in Chartres cathedral. It has eleven circuits and after many twists and turns ends up at the centre, which takes the form of a six-petalled flower. A number of us walked it and experienced its ability to focus and calm the mind.

The Rustenberg manor house garden is set around beautiful Cape Dutch buildings. Inspired by Sissinghurst, the garden has been laid out as a series of ‘rooms’.

These eventually lead to an incredibly long double herbaceous border with views towards the Simonsberg mountain.

Though the garden is essentially English in style, a couple of details reminded me of Mediterranean France – the beautiful, though very large, cork oaks (Quercus suber) and a charming ‘terrasse végétale’ in front of the house.

Text: Christine Daniels

Photos: Christine Daniels, Sandra Cooper and Sara Robinson

Gardens of Betty’s Bay, in the Kogelberg Nature Reserve

The Harold Porter Botanical Gardens

A beautiful drive along the coast and into the Kogelberg Nature Reserve to Betty’s Bay brought us to the Harold Porter gardens, 10 hectares of which are cultivated, with the remaining 190 hectares being natural ‘fynbos’, encompassing mountain slopes and deep gorges, marshes with restios, sedges and bulbs, and coastal dunes with salt-adapted plants. This was our first introduction to fynbos, the shrubland which forms the main component of the natural vegetation of the Cape.

We were to learn much more about fynbos during our tour and this vegetation type is explained in more detail in the ‘Botanical Walks’ section of this report. However, the Harold Porter garden was the perfect start, as educational panels gave us our first insight into the breadth of South African flora and we were able to see examples of the four main fynbos families: restios, proteas, ericas and geophytes.

Forty years ago the area was a forestry reserve, but then a fire cleared the vegetation and the garden began to be established. As in almost all the gardens we were to see, mountains encircled the planted spaces.

The cultivated area is divided into a number of gardens demonstrating indigenous plants which grow on different types of soils, including limestone, sandstone and shale. The idea is to encourage landowners and gardeners to cultivate plants and trees adapted to the specific soil types.

Some examples:

The cultivated gardens is surrounded by natural vegetation, through which trails have been created.

A protea garden in Betty’s Bay

This garden was started seventeen years ago by Vicky, a botanical artist and her husband, Robbie.

Their concept was to cultivate only indigenous plants, with no watering at all during the dry season. Many plants have arrived as a result of bird activity, with seeds being brought in from the wild.

Robbie became interested in propagation and decided to cultivate a range of proteas (which Vicky could then draw) and in particular to try to grow rare varieties with a view to saving them from extinction.

One of the proteas currently being propagated is Orothamnus zeyheri, the marsh rose.

This plant is on the ‘at risk of extinction’ list, after having been unseen for over 100 years, and is a plant that needs fire or smoke to enable germination.

Gardens of the Elgin valley

The Elgin valley is one of the most humid parts of the Cape, receiving around 700mm of rainfall each year.

This gives garden owners the opportunity to cultivate plants which would not survive in the more arid regions.

Fresh Woods

Peter Knox-Shaw’s parents began to develop this garden over 70 years ago, and during the 1950s started to grow species and heritage roses.

Peter and his wife Barbara have continued to collect roses – they now have 380 varieties.

The 4.5 acre garden also includes rhododendrons, wild hydrangeas, deutzias, cyclamen, epimediums, lilies and over 70 varieties of Japanese maple.

Narrow paths wind through borders filled with flowering shrubs and ornamental trees, then lead to a woodland garden under pine trees and through a small plantation of bamboos.

Plants in the woodland garden, in semi-shade:

Fairholme

The second Elgin garden, Fairholme, is much newer and, at nine acres, even bigger. It is attached to Fairholme Nursery which specialises in perennials and grasses and these are evident throughout the garden.

Other features include a parterre, a walkway under a rose-covered pergola and a woodland garden.

Keurbos Nursery Garden

Jessie Walton’s Keurbos garden was designed to attract birds, which she loves to photograph, and to showcase the plants she propagates and sells in the nursery. There are collections of bulbs, acers, azaleas, rhododendrons and heritage roses.

We enjoyed the plant combinations, particularly the roses mixed with honeysuckle, nigella and sweet peas. There were a number of lovely trees, including Actinidia deliciosa, the kiwi fruit tree, in full flower and a kapok tree.

This was also the first time we came across an example of Vachellia xanthophloea, the fever tree, so named, Jessie told us, because people noticed that wherever it grew people became sick with fever

Subsequently it was discovered that the tree liked to grow near marshes, which also attracted mosquitoes, and it was the latter that caused the fever. Even so, the name has stuck.

Some interesting plants:

Auldearn

Jenny’s garden sits on the top of a hill surrounded by apple tree orchards. She said they chose this very windy site for the views and because it was no good for apple trees. At the entrance is a lovely tulip tree, Liriodendron tulipifera, then we were led along a path lined with Nicotiana ‘Limelight’ to a pool with views to the Kogelberg mountains.

The path continued along the top of a steep slope covered in self-sown watsonias and Neomarica gracilis. This plant is known as the walking iris, due to its habit of self-propagation through new plantlets which are formed at the tip of the flower stalk, which then bends to the ground and takes root. We also spotted some rather wonderful grasshoppers.

Turning, we came to a lawn, edged by a rill and wide flower borders. Jenny has great skill in putting together pleasing colour combinations, mixing shrubs, perennials and bulbs.

We meandered on, always with the views of the faraway hills, sometimes with a foreground of orchards of Pink Lady apple trees and everywhere colourful flowers.

On the road towards Franschhoek (Dutch for ‘French corner’) some of the place names had a familiar feel: Languedoc, Le Pommier, Allée Bleue, La Petite Ferme…

Montpellier

The construction of the Montpellier house and garden, in their dramatic mountain setting, commenced thirteen years ago.

First, terraces were created, then the house was built, in Provençal style, using crushed rock for the render. Large mountain boulders were carefully placed around the garden, a staircase was constructed up the mountainside and 800 olive trees, all Italian varietals, were planted. The garden was designed by landscape architect, Ann Sutton (we would be seeing more of her work soon as she designed the gardens around The Vineyard, our next hotel).

At the entrance a number of fever trees had been planted and a stream fed a landscaped pond. We ascended towards the house via a stone pathway built alongside the stream gully, along which the existing flora had been enhanced by adding additional indigenous plants, to create a natural garden.

On arrival at the house we were invited to climb even higher which gave an opportunity for a bird’s eye view of the garden below. Looking down, the influence of Nicole de Vésian was clear – the owner later described the garden as ‘La Louve with indigenous South African plants’.

An interesting rock formation was pointed out, with Cape granite in juxtaposition with sedimentary sandstone.

Returning to the house we admired the rockery built from giant boulders, a succulent garden, a tiny walled vegetable garden and paths lined with clipped evergreens and Mediterranean plants.

Signature plants in this garden:

Delaire Graf

This impressive wine estate, where we had a superb lunch, is surrounded by a contemporary garden designed by Keith Kirsten and Raymond Hudson.

Paths are lined with plantings of indigenous and Mediterranean plants, interspersed with sculptures, many by Dylan Lewis.

Once again it was the setting, with rolling vineyards stretching out towards the Simonsberg mountain, that lingered in the mind.

Tokara

The Tokara farm, on the crest of the Helshoogte Pass between Stellenbosch and Franschhoek, was bought by the Ferreira family in 1994. It was decided to plant vineyards and olive groves, and to create garden around the house. We were guided by Anne-Marie Ferreira, the owner, and Wendy Atwell, the horticulturalist.

The visit began with a walk through the woodland garden where indigenous shade-loving plants including ferns, clivias, crinum and dietes have been established to create an under-storey beneath the trees.

Then we came upon the house, which has been re-built as a modern version of a Cape Dutch farmhouse, the original having been destroyed by fire.

Paths led on to a Japanese garden, with maple trees and flowering cherries, then steps led down to a sweeping lawn and a lake with a charming boathouse.

We moved on, past a camomile lawn, along paths where Pratia angulata had been encouraged to self-seed amongst the paving stones, through more woodland to a cutting garden. The aim here is to have flowers available all year round and there was an abundance of choice the day we visited.

Next came the vegetable garden and the orchards – bizarrely, the citrus tree area is fenced off because the staff can’t resist eating the fruit, whereas there is no such issue with the apples, pears and vegetables.

This was the final visit of the Stellenbosch leg of our trip, so after goodbyes we set off for Cape Town and the Vineyard Hotel, in the suburb of Claremont, our home for the following few days.

Text: Christine Daniels

Photos: Christine Daniels, Sandra Cooper and Sara Robinson

Gardens of Cape Town

Green Point Biodiversity Showcase Garden

Cape Town’s Green Point Urban Park, which was built for the 2010 World Cup, has views to Table Mountain, Signal Hill and Cape Town Stadium.

Within the park, the Biodiversity Showcase Garden was created to educate and inspire local people and visitors by its displays of more than 300 varieties of indigenous plants.

We were guided by Marijke Honig, a Cape Town landscape designer, who had recently completed a major replanting of the garden. Marijke explained that the area used to be a seasonal wetland pasture, used by hippos, and that the soil is clay, with poor drainage.

They therefore added 300mm of sandy soil before planting started. The garden is divided into areas which demonstrate plants which can be useful for food, for medicine, for constructing household articles, for attracting wildlife, for making hedges etc.

Marijke also chose four frequently occurring vegetation types and created gardens to illustrate how they can be replicated by people in their own gardens. The Cape area has 23 different vegetation types, so is much more complex than that which we are used to in Mediterranean France. The four gardens she created demonstrate plants of lowland fynbos (sandy acidic soils on the coastal plain), mountain fynbos (occurring on mountain slopes with dry, hot conditions in summer), renosterveld (rich clay or silty soils) and strandvelt (sandy alkaline soils near the sea).

Each section has an illustrated information board explaining the soil type, how to identify it and which plants will thrive in it. We learned that the Protea genus, also known in South Africa as ‘sugar bush’ has a wide variety of forms and flourishes under different conditions.

Here are three examples:

The Company’s Garden

The Company’s Garden, located in central Cape Town, takes its name from the Dutch East India Company who started the garden in 1652 to grow fresh vegetables and fruit to replenish their ships as they rounded the Cape of Good Hope.

The first Cape wine was produced in 1659 from grapes grown in the garden. It is now used as a public park and has a number of fine trees and a re-created vegetable garden.

The oldest tree in the garden is a pear tree, Pyrus communis, believed to have been brought from Holland by the early settlers, in around 1655. Despite the tree’s age, edible fruit are produced every autumn.

There are also wonderful examples of Spathodia campanulata, the African flame tree, Euphorbia pulcherrima, the poinsettia tree, Ficus elastica, the rubber tree, Grevillea robusta, the silky oak, and Aloe bainesii, at 17m the tallest of the South African tree aloes.

At the park’s centre is a commanding statue, erected in 1908, of Cecil John Rhodes, his arm outstretched and pointing north.

It is named ‘Your hinterland is here’ and is said to express his interest in the lands to the north of the Cape.

Kirstenbosch National Botanic Garden

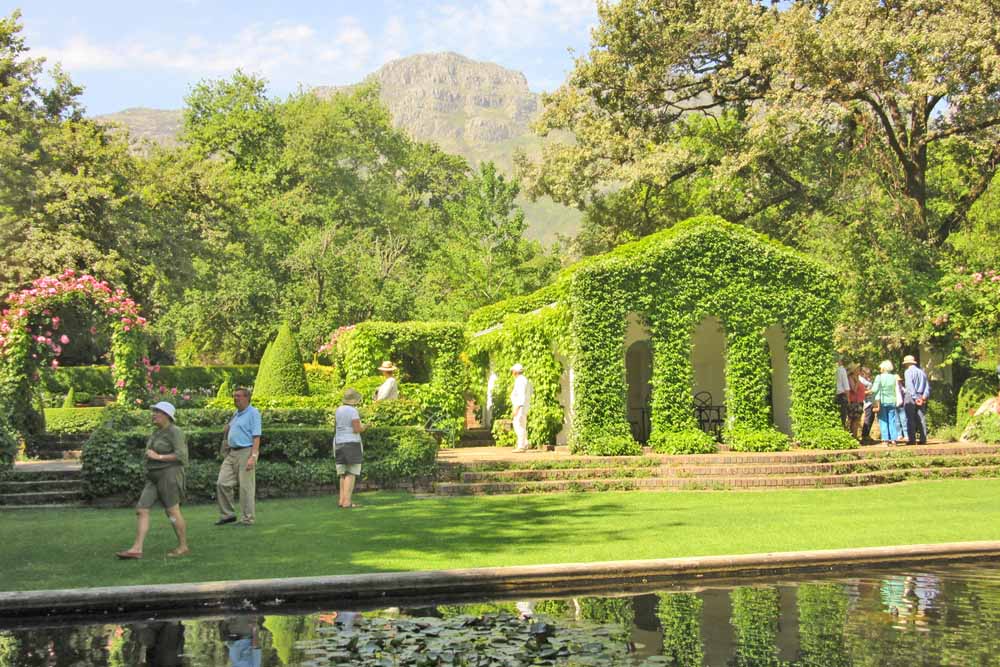

Dot Malan, our venerable Kirstenbosch guide (she is almost 90 years old and has an encyclopaedic knowledge of South African plants) explained to us that Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden is one of the seven great botanic gardens of the world.

It was established in 1913, on 365 hectares of land bequeathed to the government by Cecil Rhodes, and has a magnificent setting at the foot of the eastern slopes of Table Mountain.

Although almost all the plants in the garden are indigenous, notable exceptions are the trees planted by Cecil Rhodes in 1898 along what is now Camphor Avenue, where our visit started. Apparently this planting was done with a view to attracting Queen Victoria to visit the garden, though she never did so.

The trees include Cinnamomum camphora from China, Ficus macrophylla from Australia and Pinus pinea from southern Europe and provide shade for an under-planting of Clivia miniata. The avenue led us to the bulb house, normally closed to the public, but opened specially for us.

Here we saw a collection of the beautiful and the rare, all carefully pollinated by hand. Insects are excluded so that unwanted pollination doesn’t occur. Most of the bulbs had recently finished flowering, but we were able to see a new species, Clivia mirabilis, discovered 10 years ago, and some rhodohypoxis varieties which grow at high altitude in the Drakensburg mountains.

We learned that freesias, gladiolus, clivia, tulbaghia and pelargoniums are all of South African origin and were introduced into Europe in the early 1800s. And we also marvelled at the size of some the boophone bulbs, two thirds of which are visible above the ground.

Next, we visited the conservatory, a purpose-built desert house designed to keep plants dry.

It has a baobab tree at its centre and sections which display plants from the various arid regions of southern Africa.

From here we moved outside, with time to view just a few of the many different gardens, each one dedicated to a different climate type or plant group. Dot started with the aloe garden, because, she said, “Aloes are South Africa” and 155 different species are displayed. Our attention was drawn to Aloe arborescens x ferox, which has medicinal properties similar to A. vera and we marvelled at Aloidendron barberae, a tree aloe which grows to 22m tall and has pink flowers in early winter.

Towards the edge of the garden we came across the Brabejum fence, also known as Van Riebeeck’s hedge, as it was constructed by early settler, Jan van Riebeeck, in 1659 as part of a defensive barrier to keep out local Khoikhoi people. He planted Brabejum stellatifolium trees as they have a curious sideways growth and are difficult to penetrate. They also have a fruit which looks like an almond but is poisonous if eaten raw.

Next came the ‘Boomslang’, literally, ‘tree snake’, a tree canopy walkway made of tubular steel and African hardwood which curves its way through the treetops enabling close up views of the tree foliage, wonderful vistas of the mountains beyond and a view of schoolchildren playing on the lawns below.

We wandered on, through the cycad garden where all the plants are now micro-chipped following the theft one night of a number of long-established specimens, past Colonel Bird’s Bath, built in 1811 in the shape of a bird, and to an enclosure where some spotted eagle owls were nesting. Finally, and for me the star of the show, the fynbos walk, with its separate areas featuring ericas, restios, buchu and proteas.

The garden displays a vast number of plants from the protea family:

…and many beautiful pelargoniums:

We were to see many of these plants again, growing in the wild on our walks on Table Mountain and the Cape Peninsula.

Finally, we collapsed under a shady tree to rest our legs and contemplate the view.

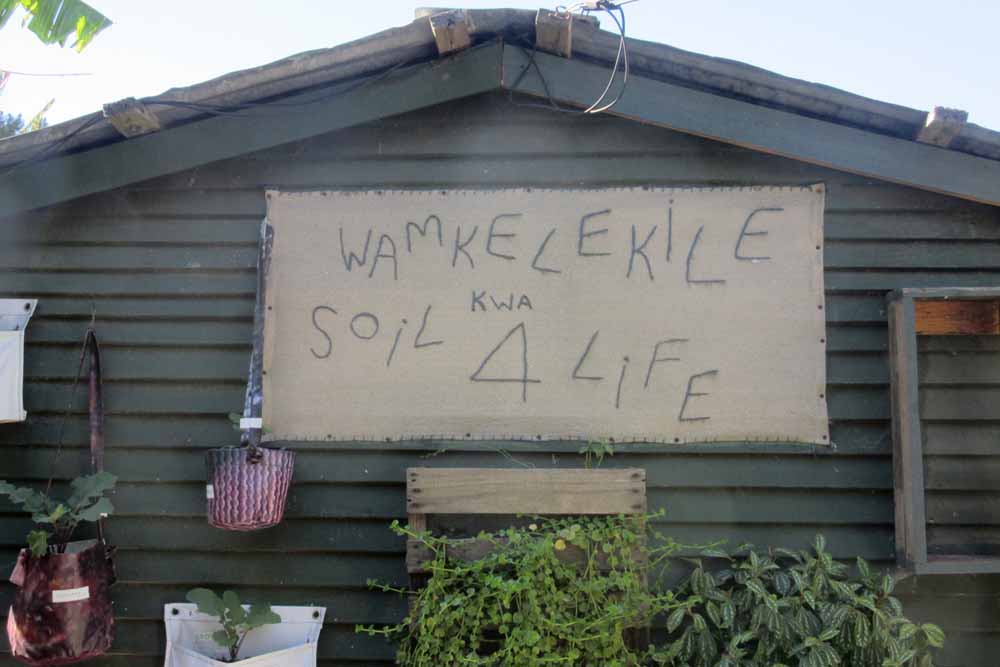

Soil for Life

Later that day we were to visit a garden just as inspirational as Kirstenbosch, but for very different reasons. Soil for Life is a self-funding organisation that assists communities in the Western Cape to overcome hunger, poverty and unemployment through the establishment of food gardens. Pat Featherstone, the founder, introduced us to Prince and Dixon who took us on a tour of the garden, which acts both as a demonstration area and as an income resource.

The demonstration garden shows how vegetables and fruit can be grown in small spaces, using very little water. There is much use of homemade compost and mulch and re-cycled materials. Vegetables are grown in raised beds surrounded by logs to prevent mulch from being washed away in rain storms. Stepping stones are used to avoid compacting the soil, which is improved with organic matter before planting. Watering is done via plastic bottles inserted into the soil.

Vertical gardens are created in pallets and tyres to show how vegetables can be grown in places where no land is available.

Prince and Dixon also took us to the section of the garden dedicated to the production of compost and mulch. Staff and volunteers collect rotten vegetables and fruit from supermarkets, straw and manure from stables, leaves off the streets, grass mowings from roadside verges and woody material from trimming trees and shrubs in their own and local residents’ gardens.

All of this material is mixed in large heaps, turned and watered lightly once a week, covered in black plastic and then, in about eight weeks’ time, bagged up and sold to the public for 35 rand (2.50 €) per bag.

Gardens of the leafy Cape Town suburbs

Stellenberg

Stellenberg, situated in the southern suburb of Kenilworth, is one of Cape Town’s finest country estates. Established in the 18th century, and still a family home, it has lawns with ancient oak trees and a series of garden rooms, each with its own character.

We entered through the ‘werf’ and started our tour on the eastern side of the house which gets afternoon shade, so is used as an entertainment space for the evenings. The planting was inspired by the white garden at Sissinghurst, but with added creams and soft pinks and some dark foliage for contrast. Clipped evergreen hedges provide structure.

The house is classic Cape Dutch and was constructed by artisan slaves brought from Indonesia and India, using sun-dried bricks, lime plaster and restio thatch. The north façade has a gable window, which acted as a means of escape in case of fires, which used to occur frequently.

On the western side is a walled garden around a swimming pool, with borders filled with blue and purple flowers including heliotrope, agapanthus, salvias, Hibiscus syriacus and Plumbago capensis.

Moving away from the house we came to the courtyard garden, previously home to a tennis court. In 1989, David Hicks was invited to create a garden in the rectangular space and his design of two halves, separated by a central axis, remains today.

The left, ‘male’ side is a French style parterre with hedges of Myrtus communis.

The right, ‘female’ side has an abundance of flowering perennials, colour-themed in four quadrants.

The walls are covered in climbing roses including Rosa ‘Albertine’ and Rosa ‘Albéric Barbier’ and along one side is the vine walk – a series of arches covered in non-fruiting vines.

Other gardens followed, one inspired by the Alchemist’s garden in Provence, another for citrus trees, then we came to a path alongside a stream shaded by a number of 80 year old Phoenix reclinata trees.

Next, we came upon a ‘wild’ garden full of prunus, cannas, oleander and ginger plants left over from colonial times, then a vegetable garden which had been laid out in a medieval pattern with a water feature at the centre and sections for vegetables, fruit, herbs and flowers.

We were shown an English oak which was in a poor state and will have to be removed. Apparently, oaks, cedar trees and camphor trees were introduced to the Cape with a view to their being grown for timber, but the oaks grew too quickly and left them vulnerable to rot and disease. The local hardwood, Podocarpus latifolius is now grown for timber instead.

Greystones

In 1869, Dirk’s great-grandfather arrived from Lübeck in Germany and had a house built on the crest of Wynberg hill, in the style of his European home. The garden was created by Dirk’s mother, the author, Mary Muller, a keen collector of ‘exotic’ plants from all over the world.

More recently Dirk has been adding more indigenous plants to this garden which has deep, acid soil. From the terrace, there is a stunning view towards the sea at False Bay and the Cape Peninsula. To one side is a magnificent Millettia grandis, whose Zulu name is the umzimbeet tree.

We walked along woodland paths past azaleas, camellias and gardenias and enjoyed the scent from a tropical, evergreen shrub, Murraya paniculata.

Soon we came across a huge rock, which Dirk had loved to climb as a boy, so of course, a number of us felt we had to do the same…

As we emerged, the garden changed style completely. An arid garden with aloes and boulders led through borders packed with indigenous plants to a flat area which turned out to be the site of another no-longer-used tennis court.

Here Dirk had introduced a mixture of fynbos and Mediterranean plants which thrive on very little water. Ballota, cineraria, euphorbias, pelargoniums, felicia, Eriocephalus africanus and many varieties of mesembs crowded together in colourful disorder.

Soetvlei

Our final garden of the tour, in Tokai, could not have been more different. Our host, Sheila, led us to a charming outdoor ‘theatre’ where she explained that only three years ago, there had been no house, no garden, no trees, no planning permission, just eight acres of unappetising clay with stagnant puddles.

She and her husband were given permission to build a new house in Cape Dutch style, with a thatched roof, and to put in land drains in order to be able to create a garden. The government laid down strict rules about what plants could be planted where, specifying that only endemic plants be introduced to garden areas at a certain distance away from the house.

The garden, designed by landscape architect, Patrick Watson, stretches out behind the house in a series of formal terraces, marked out by topiary obelisks. Although the planting is new, the bones of the garden are clear, with roses on pergolas and in pots providing colour.

To one side is a vegetable garden, laid out in raised beds and designed to be decorative as well as useful. A charming informal touch is the way violets are encouraged to self-seed in the gravel behind the house.

Further away, large square plots have been mono-planted both with indigenous plants, including a stunning bed of Gomphostigma virgatum, and with Mediterranean species such as Orlaya grandiflora.

To one side, paths lead towards the vines which have been interplanted with gaura.

Returning to the house, we came to a beautifully planted eco-pool, complete with hippo…

And finally, tea.

Our thanks to all the garden owners for the warm welcome and generous hospitality, and most especially to Angela, who researched, planned and organised this unforgettable trip.

Text and photos: Christine Daniels

Botanical walks on the Cape Peninsula

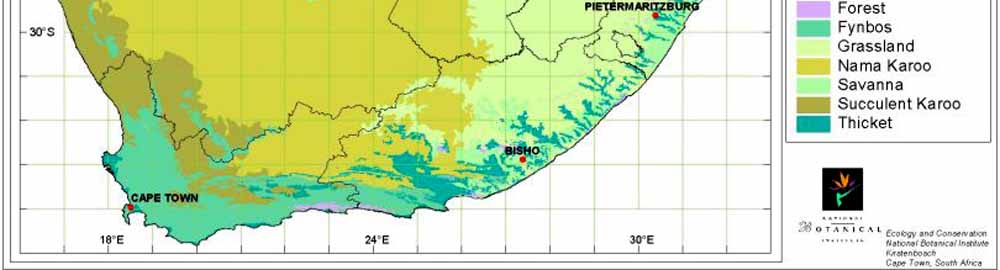

I arrived in South Africa with a vague understanding of the word ‘fynbos’ as being one of the many terms used in different parts of the world to describe Mediterranean-climate vegetation (maquis or garrigue in France, phrygana in Greece, mallee in South-Western Australia, chaparral in some parts of California, matorral in Chile). In fact, fynbos, (pronounced fain-boss, and derived from the Dutch word fijnbosch, meaning fine leafed bush, is the name for a vegetation type specific to the south-western tip of Africa.

In these 48,000 sq. km, an area roughly equivalent to that of Mediterranean France, are over 7000 species of plants (as a comparison, there are 25,000 in the whole of the Mediterranean basin). This very rich diversity, coupled with the fact that 80% of the species are endemic, made our botanical walks across the hilltops of the Cape Peninsula, in the company of expert botanical guides, a very special experience.

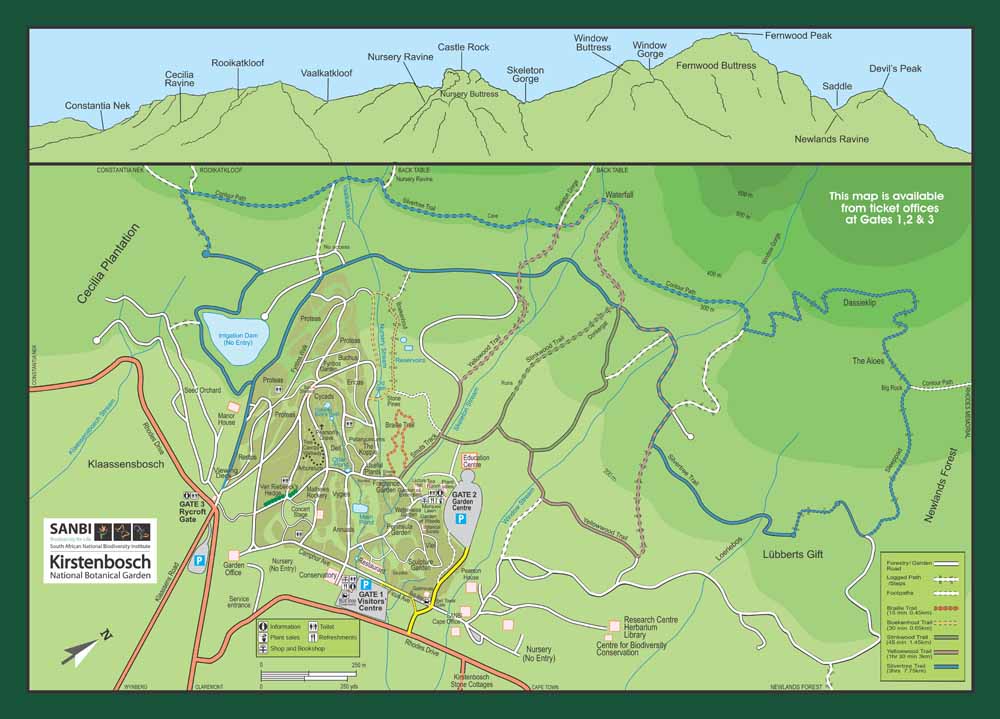

Map: National Botanical Institute, Kirstenbosch

We walked in two areas of the Cape Peninsula National Park and up the side, and along the top, of Table Mountain. Botanical information was supplied by Callan Cohen, a natural historian and founder of Birding Africa and a group of Kirstenbosch guides. They explained that fynbos has four elements:

- Restioids: shrubby grasses, sedges and reeds with reduced or absent leaves and tough, wiry stems

- Ericoids: ericas and other heath type shrubs with small, narrow or needle-like leaves

- Proteoids: tall and medium sized shrubs, mainly of the protea family, with broader leaves

- Geophytes: bulbous plants

Fynbos vegetation occurs predominantly on well-drained, infertile soils and relies partly on fire for regeneration. It needs to burn every ten to forty years in order to sustain its plant diversity, with some species storing their seed in fire-safe cones for release after a fire and others re-sprouting from the base. We were to see a number of examples of this during our walks.

Walk 1: Kleinplaas Dam

Sara and I met Callan at a small car park in the hills above Simon’s Town and set off for Kleinplaas Dam. Callan explained that he was a botanist as well as an ornithologist, with a keen interest in all forms of wildlife.

Not only was he able to identify almost every plant we saw, he also entertained us with interesting explanations of the pollination methods used by different species.

Alongside the track were vivid pink pelargoniums, osyris, coleonema, whose leaves had oil glands on the back, releasing a sweet smell when crushed, bright yellow leucospermum, aspalathus, like a gorse bush, leucadendron (the cone bush),

Metalasia muricata, with honey-scented flowers, the red seed capsules of Trichocephalus stipularis, Mimetes cucullatus, which Callan said was pollinated by ants and the brilliantly white Syncarpha vestita, locally known as Cape Snow.

As we reached a plateau area, the appearance of the vegetation changed. There had been a fire here in January 2016, so we could see re-growth between the still-standing skeletons of the shrubs

It was amazing to see how the leucadendron cones had survived the fire and had subsequently released their seeds.

Emerging from the very sandy soil was a carpet of the pale pink flowers of Geissorhiza bonae-spei, which Callum told us was actually an iris and only to be found in very few places.

He said that geophytes are to be found in much greater abundance after a burn. Close inspection revealed other tiny flowers hidden in the grass, including Ixia dubia and variously-coloured morea.

This area also had some new plants, the Psoralea pinnata bush, which we were later to see in the form of a medium-sized tree in the Harold Porter garden.

Low-growing, in the almost white sand, was the silvery Petalacte coronata and a pink version of the more usually violet, Pseudoselago serrata.

Further on, in a slight dip, was a peat bog with restios and low shrubby growth. Callum said that here we should look for orchids and soon we started to spot them, first the beautiful

and very rare Disa purpurea, then Holothrix villosa (the toothbrush orchid), Disa bilvalvata , which only appears after fire, the pink spikes of Disa versicolor and the dramatically-coloured Disa atricapilla, pollinated by wasps.

The sandy path continued, now lined with watsonias in pink and orange, Wachendorfia paniculata, in yellow and orange, and two other plants which appear after fire, Erica cerinthoides, also known as fire heath and Schizaea pectinata, an interesting fern.

Eventually we arrived at Kleinplaas Dam (or reservoir) which had the appearance of a very beautiful lake.

As we turned to make our way back, Callan noticed a largish group of baboons on the hillside in the distance.

Then, as though from nowhere, several appeared on the trackside. They seemed totally disinterested in us, wandered back and forth, then bounded off into the fynbos.

Walk 2: Silvermine

Our second walk was in the Silvermine Nature Reserve, in Table Mountain National Park, high above Hout Bay. This time the whole group walked, so in addition to Callan we were accompanied by a number of Kirstenbosch guides. Once again there had been a fire in the area we were walking in, this time in March 2015.

We set off on an uphill path through a rocky landscape, with the familiar burnt stems sticking up through the new growth. As we climbed there were many charred tree stumps, so this had obviously been a wooded area.

Alongside the path, we saw a few plants familiar from our earlier walk, such as Syncarpha vestita and Pseudoselago serrata, though this time more purplish than before, but the majority were new, even though we were not very far away from our previous outing. The first to stop us in our tracks was Liparia splendens, locally known as the mountain dahlia.

Then there was the gorgeous, pink-flowered Lachnaea grandiflora, Agathosma ciliata, whose genus name means ‘good fragrance’ and is commonly referred to as Buchu, Adenandra uniflora, a member of the citrus family, with fragrant oil glands in its leaves, Tetraria sp., a fynbos sedge, and another member of the aspalathus family, Aspalathus cordata.

Reaching a ridge, there were splendid views in all directions.

We continued along the ridge, with blackened tree stumps on all sides, some with new plants growing out from them.

Callan pointed out what looked like a mound of volcanic sand, which he explained was the mound of Amitermes hastatus – the Black Mound Termite.

We spotted more varieties of aspalathus, violet-flowered Moraea tripetala, Crassula fascicularis, Psoralea aculeata and P. pinnata, the distinctive Stilbe vestita,

a number of pelargoniums including P. longicaule, Euryops pectinatus growing out of a crevice in the rocks, and the deep blue flowers of Anchusa capensis.

The path now became more open and very sandy, and soon we started climbing again. To one side, Callan pointed out a dwarf form of the bugle lily, Watsonia coccinea, which only grows in humic soils (ie those rich in organic matter from decayed plant material), which are seasonally wet.

We admired a Chondropetalum tectorum with large bracts, which Callan said was a female plant. Restios are wind-pollinated, like grasses, and have male and female flowers on different plants. There was also an interesting flowering tree, Virgilia oroboides, about 2 metres high. Virgilia belongs to the pea family and is a pioneer plant after fire. It had grown to this height in only two years.

As the path widened, it became clear that we were approaching a view point.

We had crossed the Cape Peninsula to the western side and were rewarded by a stunning view of the Atlantic Ocean and the coastal town of Hout Bay.

Angela led us to a group of rocks and we settled down to eat our picnics and admire the view. We were joined by a curious and hungry redwing starling, which Angela eventually had eating out of her hand.

Then it was time to return to the car park, finishing our walk alongside the waters of Silvermine Dam.

Walk 3: Table Mountain

This walk was undertaken by just four of us, Kirsten, Bruce, Sara and me, and was more of a hike than a botanical walk, but we did see some interesting plants that we hadn’t seen on the earlier walks. Kirsten has written a great blog, Conquering Table Mountain, in which she accurately describes our “ a very challenging, yet exhilarating day” in great detail, so I’ll confine myself to the highlights and the flora.

When we were at Kirstenbosch, our guides had pointed out the beginning of the track up Skeleton Gorge, which leads to Maclear’s Beacon, at 1084m, the highest point on Table Mountain. They said this was a great walk and that we could then continue along the top to the cable car for the descent. We had one day to spare at the end of the trip so the opportunity was irresistible.

Kirstenbosch is at 132m, so we knew were in for a pretty steep climb. Skeleton Gorge is wooded and shady, with a stream tumbling down it. In between the rocks were ferns and lots of Zantedeschia aethiopica, the arum lily. In places, ladders had been helpfully positioned to get across the boulders, then it was a case of scrambling up the stream until we emerged above the treeline and, for the first time, were able to look down upon the plain below us and, in the distance, False Bay.

The path continued uphill, through grassland covered in ferns and pelargoniums, then as we climbed, the vegetation became more shrubby, with ericas and proteas.

We saw a number of ‘new-to-us’ plants here, and Callan kindly identified them from photographs:

As we continued to ascend, we became aware of the light rolling mists which were beginning to surround us – the famous ‘tablecloth’ of cloud that sits on the top of the mountain and appears to slide down the sides.

Fortunately, visibility was good enough to continue and soon we reached the highest point, Maclear’s Beacon, around which the land had recently burned, so had a strange, other-worldly appearance.

We set off across the flat ‘table top’ of the mountain.

First we crossed the burned section, where re-sprouting leaves lit up the charred landscape, then on to an area of flat rocks and restios.

We were now walking almost due west, towards the cable car station.

The views that appeared through the mists were first of central Cape Town, Table Bay and, dimly, Robben Island, then of the Lion’s Head.

As we approached the western edge of the ‘table’ the mist lifted and it became obvious, from the lack of people on the top, that the cable car wasn’t running.

So, we took a quick scoot around to admire the now much clearer views, then had no choice but to descend by the brutally steep Platteklip Gorge.

The Platteklip gorge was described by T.P. Stokoe, photographer, mountaineer and botanical collector, as “the most damnable descent on the berg”. Born in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1868, Stokoe arrived at the Cape when he was 43 years old and over the next 48 years discovered over 150 previously unknown plants. His words about the Platteklip gorge were written in his account of his descent from a climb he made on his eighty-ninth birthday.

Despite the lack of light in the gorge due to steep cliffs on both sides, there were still fynbos plants thriving there, in particular, Pelargonium cucullatum. However, it required total concentration to make our way down the steep path of rock and scree, so we looked at nothing but our feet for the next hour and a half.

Eventually we emerged onto Tafelberg Road, where taxis were waiting to pick up the few walkers who had hiked down the mountain.

A long but wonderful day, never to be forgotten.

Text and photos: Christine Daniels

Wildlife seen in gardens and on our walks

Whilst walking in gardens and in the countryside, we saw many examples of animals, birds and insects that were new to us.

Here’s a selection:

Birds

The hadeda ibis (Bostrychia hagedash) has a loud and distinctive call – ‘haa-haa-haa-de-dah’. We saw and heard these in Stellenbosch gardens and in Cape Town.

The tiny prinia, or wren-warbler, spotted at Keurbos nursery garden, feeds on insects. The red wing starling (Onychognathus morio), with its beautiful chestnut-coloured flight feathers was seen on the Silvermine walk.

We spotted the malachite sunbird (Nectarinia famosa), which feeds mainly on nectar, in an Elgin garden.

The Cape sugarbird (Promerops cafer) has a beak adapted to feed on the nectar of proteas. It is endemic to the fynbos biome.

As well as its famous flora, Kirstenbosch is also home to several types of fauna. The resident family of spotted eagle owls (Bubo africanus) had recently had chicks (owlets).

Kirstembosch also hosts a ‘confusion’ of helmeted guinea fowl (Numida meleagris), endemic to southern Africa and noted for their colourful heads.

Sara and I saw a colony of African penguins (Spheniscus demersus) on our trip to Robben Island, and Sandra and Allan visited the penguin colony at Boulders Beach, on False Bay.

The African penguin was formerly known as the jackass penguin because of its distinctive bray.

Mammals

Several brown fur seals (Arctocephalus pusillus) were basking on the beach and posing for photographs on the rocks in Kalk Bay.

These male Chacma baboons (Papio ursinus), wandered across the track during our Kleinplaas Dam walk.

A ranger was encouraging them not to wander towards suburban areas, where they sometimes go foraging for food.

Sandra spotted this beautiful springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis) on land adjacent to the garden at Paradyskloof. The name springbok comes from the Afrikaans words ’spring’, meaning jump, and ‘bok’ meaning antelope.

Insects

The koppie foam grasshopper (Dictyophorus spumans), is indigenous to Africa, and we saw it both on walks and in gardens.

It can be seen in various strong colours from black to a reddish orange. The ones we saw were about 60mm long.

We spotted a number of the egg sacs of Palystes castaneus, the huntsman spider, attached to foliage in the garden at Tokara. They were around 80mm long.

The mound of the Black Mound termite (Amitermes hastatus) was seen in very sandy soil at Silvermine, and had a diameter of about 300mm These mounds are built above subterranean nests.

Reptiles

This Southern Rock Agama (Agama atra), was very well camouflaged, apart from its turquoise-blue head, as it sat in the sun on a rock near to Kleinplass Dam.

Apparently, the heads of the males take on this bright blue colour during the breeding season!

Text: Christine Daniels

Photos: Christine Daniels, Sandra Cooper and Sara Robinson

Masiphumelele Township

Twenty years ago, when we were looking for a house to buy in the Vaison-la-Romaine area of the Vaucluse, some long-standing friends and work colleagues, Sue and Andrew Smith, were a tremendous help. They had been living in France for some time, and loved it. Some years later, they visited the Cape area of South Africa, and from that time put down roots there too, spending six months of every year in each hemisphere.

Sara and I went to stay with the Smiths, and were privileged to have them show us round a nearby township, Masiphumelele, where Andrew works as a volunteer, for a charity called Masicorp.

Masicorp provides funding for education, and investment in enterprise so that the people of Masiphumelele can escape from poverty. In Masiphumelele most people live in shacks. Six families or more share one water tap and toilet facility. Roughly 70% have no regular work. Even for those with work, incomes are very low. The township suffers from poverty-related health issues: more than 20 % of residents are HIV/AIDS positive and life expectancy is under 50 years.

Masicorp has built a library and education resource centre, a pre-school unit, and funded projects to introduce Maths, English and Science labs into the primary school. Our visit started with Masi’s recently opened pre-school educare centre, where we saw 160 children from a few months old to six years being cared for and given pre-school education. Everything was of a very high standard, so not surprisingly the waiting list for places is huge – there are about 2500 children between the age of 1 and 6 years in Masiphumelele and of these around 1500 attend some sort of crèche or educare centre in the township.

Next, we visited the primary school, first the maths lab, where we got involved as the children had their regular ten minute break for physical exercises, then the science lab, where the subject happened to be soil analysis.

The white board explained the differences between sand, clay and loam and on the table were containers with the different sorts of soil for the children to feel. I asked the teacher if the children were taught how to analyse the soil near their homes, with a view to growing plants for food, and suggested the jam jar method. (see David Bracey’s explanation at our soil workshop). Within moments the teacher had introduced me to the class and informed the children that I was going to explain to them how to analyse soil using a jam jar and water! So, I found myself giving an unexpected and impromptu short lesson in soil analysis and why it is important to know one’s soil type.

We moved on to the library, stocked with books and magazines for all ages, then looked at the education resource centre, equipped with computers for people to use and where classes in computer skills are held.

The visit was enlightening, inspirational, shocking and moving. The work being done by the charity is superb. However, the scale of the problem is vast. The population living on Masiphumelele’s 45 hectare site was estimated to be 38,000 in 2010. We were told that it is still growing, mainly due to the arrival of economic migrants from other African nations. This was obvious from the number of tiny one-person shacks crammed into the backyards of many of the single room homes. Apparently, these shacks are rented out to immigrants, to provide extra income.

Notwithstanding this, the people we talked to, teachers, shop-keepers, volunteers and young people, were smiling and full of hope. We heard many heart-warming success stories and were awed by the optimism and sense of purpose of the people running the charity and the staff and children in the schools. We felt very lucky to have been given the opportunity to have an insight into this different side of South Africa, without which our trip would have been incomplete.

To read more about Masiphumelele, and Masicorp’s work there, visit their website.

Text: Christine Daniels and information from Masicorp’s website

Photos : Masicorp

![]()