Garden Diaries / Journaux de jardins

A Coastal Garden in Roussillon

Click on the images to enlarge them / Cliquez sur les images pour les agrandir

With a gardening autobiography starting in chilly rain sodden Glasgow, followed by moist and mellow London, the culture shock of a Roussillon garden in France on the Mediterranean coast was an intriguing challenge.

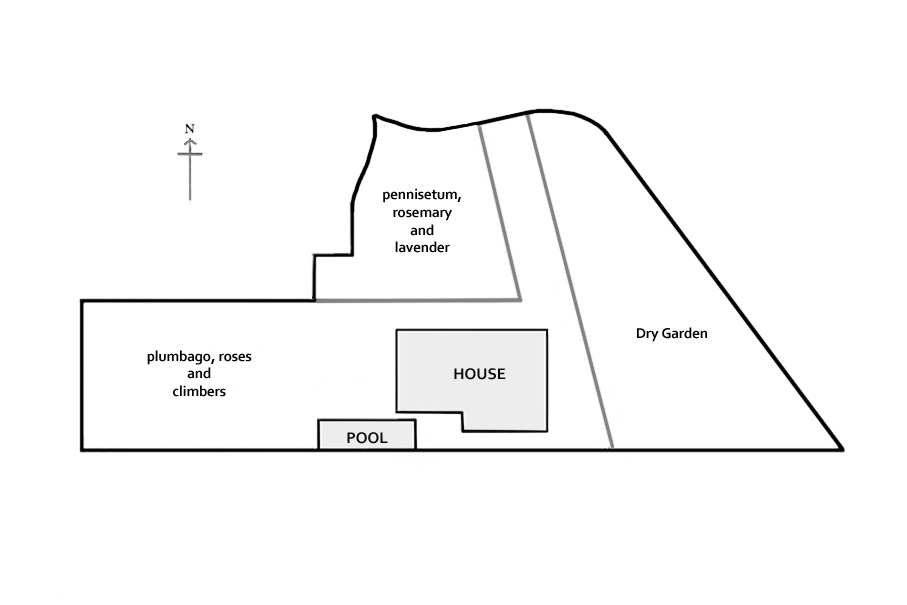

At 42°N 30’ with 300 days a year of sun, relatively low rainfall, and only occasional brief frosts, it was, as I discovered, ideally suited to many Australian and Mexican plants, so I had a new template from which to paint a garden. The main section of the garden faced south, the front north and the dry garden east. The soil was acidic, extremely stony, turning to dust in summer.

My initial design response was sheer panic at the haphazard weed and tree strewn main area, with not one piece on a level with anything else. It sloped up, down, sideways, wherever you looked. Alan Titchmarsh may start with a carefully considered overall design on paper but for us lesser mortals it’s about exerting control over ten square feet at a time and praying all the bits will pull together somehow at the end of five years.

Lavender – of unknown variety since French and Spanish nurseries don’t fuss too much with detail – was planted in an oblong around plastic sheeting covered with volcanic ash with an elegantly sparse Eriobotrya japonica (neflier) and a nectarine tree inside.

So initially there was one area of sanity in a wilderness of ferociously relentless weeds which sprouted, spread their seeds and subsided only to hand the baton onto their eager brethren-in-waiting. Mimosas sneakily thrust their subterranean roots everywhere. Lavateras popped up beside seedling pines.

I’m no great distinguisher between weeds and cultivars. If it’s pretty, it can stay. The ribwort plantain (Plantago lanceolata) made an elegant statement solo, with its seed heads standing proud, until I discovered it was followed by several hundred of the same ilk. If you spied it at Chelsea in one of the competition gardens and were tempted, be warned. The wild geraniums and field marigolds were cute, but likewise too much of a good thing and had to go. Umbilicus rupestris stays since its spiky pink flowers brighten the spring then fade to nothing. And I hadn’t the heart to remove the friendly wild violets which the previous owner bequeathed to me in quantity. They bounced in like a pet that knows it is adored and won’t be rejected, flower happily, were pulled up as they faded and reappeared the next year.

Several large mimosa trees were cut down much to the neighbour’s relief since the seeds clogged his swimming pool filter. Sixteen parasol pine trees were despatched in an afternoon by my first helper, an excitable Frenchman with a serious coke habit. In a hyper-manic fit he also mistakenly turned his chain saw on a giant grey aloe blocking the drive way. Despite their health giving name the juice causes an allergic reaction on the skin. He was covered in hives.

Like most ex-pats I arrived with memories of dainty snowdrops and bluebells, blousy clematis, busy lizzies and green swathes of grass which were too comforting to let go. Some were tried on the unyielding terrain, all summarily despatched by months of scorching summer sun. Gradually I tossed out all my old ideas and learned to love euphorbias and succulents, neither of which had been favourites before. In this climate you develop a more than healthy respect for the indigenous plants such as the vines which stay green on the parched hillsides with no rain for five months. Ditto Euphorbia characias, deemed ‘exotique’ in England but growing wild beside the mountain road to Spain, a splash of grey-green where you think nothing could survive.

I also arrived with spade, fork, hoe and trowel. The soil, standard vineyard dust and rubble with mountain rock close to the surface, was entirely spade resistant, so they all had to be tossed away in favour of a blacksmith crafted heavy iron ‘shadyk’ pickaxe which serves as hoe, hole digger, tree chopper, rock splitter – a veritable snake oil of an implement. There’s nothing it can’t cure.

One third of the garden facing south was drip-watered so there I had some latitude with plant choices, though the David Austin pale cream roses, so suited to soft English landscape, just looked wrong in the harsher Mediterranean light. Plus they acquired rust, black spot and their heads drooped.

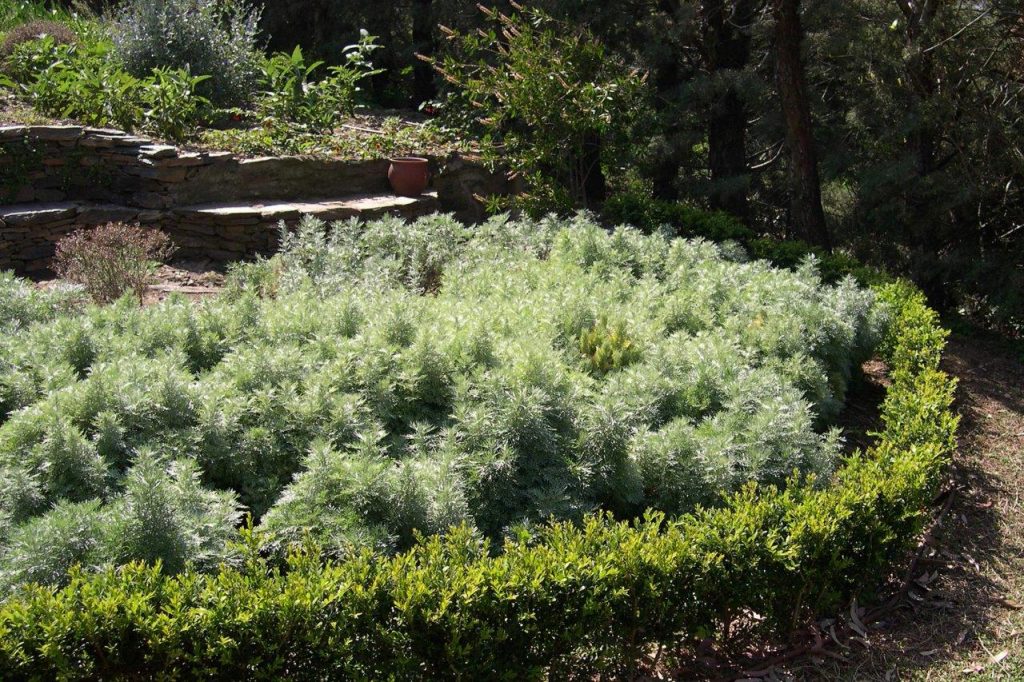

Luckily I have been well taught that the first prerequisite for a gardener is ruthlessness, so they went and were replaced by pest-resistant white carpet roses, Rosa ‘Snow Princess’ and Artemisia arborescens ‘Porquerolles’, small fluffy balls of grey.

The great successes were the climbers on the west wall including the Australian Hardenbergia violacea with its reams of purple legume flowers from January to March just when you need a lift. The brilliant pink Passiflora jamesonii exasperated my Scottish soul when it produced one flower the first year but having discovered that it thrived when fed, it then festooned itself for a good twenty yards from a burgeoning tree-like base and flowered almost twelve months of the year.

The Abutilon megapotanicum with its small yellow and red flowers also did its duty colour-wise all year round. The best climbing rose was the Meilland Rosa ‘Pierre de Ronsard’, with its luminous deep pink centres fading to cream border petals. If fed it flowered all summer.

The ornamental strawberries were undoubtedly a mistake since they galloped away, but ground cover was essential and they certainly do that. Aptenia cordifolia (succulent with tiny red/purple flowers) was also a useful ground cover if you remember to clear its dead undergrowth to keep the snails down and hack it back to the root every four years to tidy it up. The purple trailing Lantana montevidensis (such an improvement on the orange/red lantana of village tubs) blooms profusely in an exuberant swathe ten months a year beside the red, winter-flowering prostrate Grevillea lanigera ‘Mount Tamboritha’.

In summer the white Gaura lindheimeri and Pennisetum orientales grass add a dash of white. The other heart-warmer was a small field of golden Stipa tenuissima at the far corner, which was my tranquillity spot. I would sit on a shady stone bench, watching its silky tops waft gently in the breeze and sometimes wave violently, yanked by the cats playing tigers in the savannah in its undergrowth.

The blue Plumbago auriculata flourished profusely, helped by a coastal situation, giving mid-summer to late autumn colour, growing up walls, trees and in one huge freestanding bush.

The bird of paradise Caesalpinia gilliesii, a small exotic tree, also splashed up the colour scheme. But the pink-flowered Lagerstroemia indica (Cape Myrtle) was a definite mistake beside the blue plumbago – too Barbara Cartland.

Here are some photos of the south-facing garden:

Gardening to me is about having fun, experimenting and not always listening to the know-it-alls who tell you it won’t work. Asking around about methods of disguising the ugly Mediterranean pines, with their bald feet and scraggy midriffs whose tops provide a necessary wind shield round the garden, everyone said nothing grows under pines. Well it took time, and it does have leaky hose watering, but you can grow plumbago, solanum, honeysuckle, jasmine and wild wisteria beside and up pines. Though don’t try climbers on your leylandii since it kills off any foliage which is covered.

The other necessity was grass replacements since what is a garden without an oasis of flat green? Dichondra repens (tiny flat green leaves) grew wild here, takes light walking, likes a touch of shade and water but seems to survive without either if necessary – and best of all it keeps the wild oxalis at bay. Not completely, since life is never perfect, but it’s certainly a huge improvement on the Phyla nodiflora which I planted extensively in the open in full sun. Phyla is deciduous in cold winters, grows weeds like crazy between its bare roots and I discovered too late it is only 3.5 on Filippi’s scale of drought resistance – which means not very. Hint on phyla – if you get bored, as I did, with its early struggles and ladle on the grass feed, it responds with great delight, shoots up and gets too leggy.

I also experimented in the walkable-but-not-grass category with Frankenia leavis (rather too sombre green foliage, tiny pink flowers) and Achillea millefolium (somewhat messy, grey leaf, yellow flowers).

In the front square of the garden, north-west facing, old vineyard steps were planted with a long top row of Rosmarinus ‘Punta Canelle’ (tumbling deep blue, no water, no feeding, blissfully robust); Pennisetum villosum (fluffy white seed heads, appreciates some water) around an almond tree in the middle. There was supposed to be a carpet of lavender below but the less said about that the better since I gave up after the third planting.

Lavender is not the easy option it sounds, being devilishly temperamental and even when it survives getting leggy and scraggy underneath. I have a theory about gardeners, that some plants like them and will grow delightedly no matter how they are treated, while other plants have a personal antipathy and even placed in the perfect milieu will just turn their toes up out of spite. Lavender and I have parted company and won’t be reconciling anytime soon.

The bordering pines were camouflaged with bamboo, a mistake I won’t repeat since their water requirements initially are not eco-friendly.

A shady nook to the side became a small Japanese-style garden, a nonsensical idea in this climate, but some of the indoor azaleas survived outside beside the claret-leafed Loropetalum chinense var. rubrum ‘Fire Dance’, the dichondra was content and the camellia hedge did grow though impossibly slowly. Nearby the Trachelospermum wilsonii made an excellent ground cover for an awkward bare patch, an idea from New Zealand, flowering fragrant white into summer, with reddening leaves over winter. The water barrels grew water lilies along with mosquito larvae munching Gambusia affinis fish.

The two terraces around the house with long raised beds started out with bedding plants, until I became tired of the fuss and expense of twice yearly switches. So instead of the riotous petunias, portulucas and dipladenias which appeal to my somewhat vulgar need for flashy colour, I was persuaded by my second garden helper, Vincent, an inspirational gardener with quieter tastes than mine, into an elegant line of bright green Pittosporum nanum balls interspersed with the grey leaved, white flowering Convolulus cneorum.

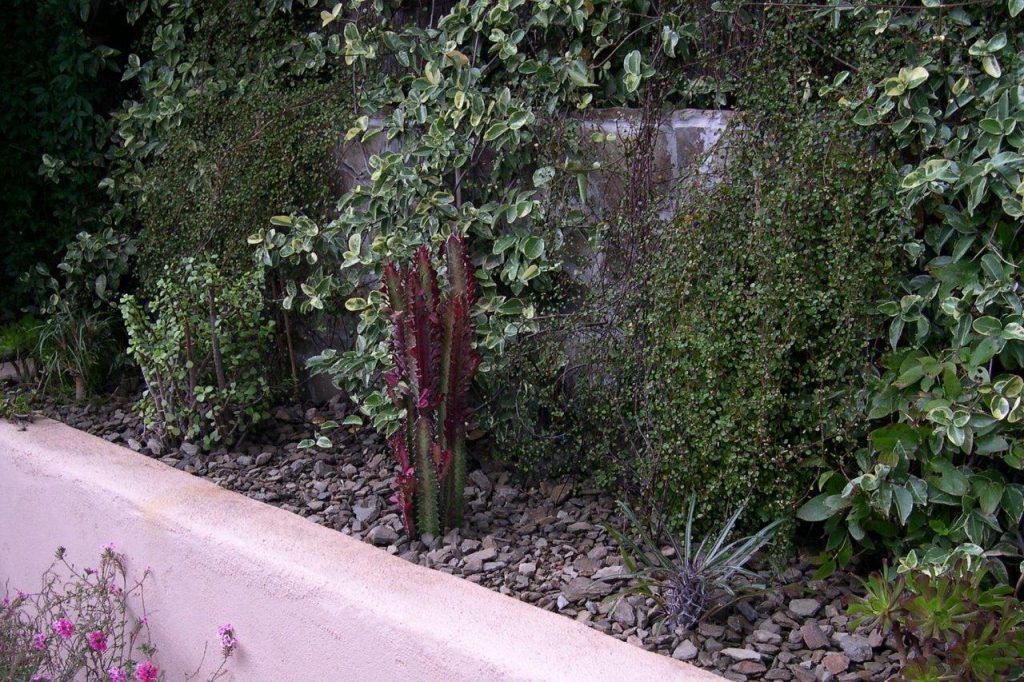

I wouldn’t have chosen it but it is a triumph. The dark green, tiny-leafed Muehlenbeckia complexa (maiden hair vine) also makes an interesting interweave with the variegated Trachelospermum jasminoides ‘Variegatum’, carpeting up a wall.

The two front triangles on either side of the main drive were a headache since they took the full brunt of the Tramontane wind which howled at positively North Atlantic pitch for days on end, had even worse soil and more mountain surfacing than elsewhere, and were edged as per usual, though not protected, by pine trees.

Feng shui, however, dictates that the entrance is of prime importance. Eventually Garry the stone was summoned, an ex-busker from Reading, who learned his new craft in the vineyards. He gave structure to the steeply sloping triangles with meticulously built small vineyard walls constructed round the protruding chunks of bare mountain rock à la Andy Goldsworthy. The local rock is grey schist which most often arrives helpfully flat from striated layers.

Eventually, after much dithering, blue was selected as the plant colour of choice to make a statement against the hard stony landscape. The pale blue Agave victoriae reginae sat star-shaped in a row above fluffy blue Festuca glauca grasses and eye-catching Euphorbia myrsinites with a line below of slender-stemmed bright blue Helictotrichon sempervirens (Kentucky Blue Grass). Across the drive in another triangle a mass of delicious blue Senecio mandraliscae (aka Kleinia repens) glowed like iridescent seaweed. The large leafed red and blue succulent Kalanchoe thyrsiflora gave a pleasing contrast to the blue hues, their rounded form softening down the aggressively spiked agaves, though they did sag badly with heavy frost.

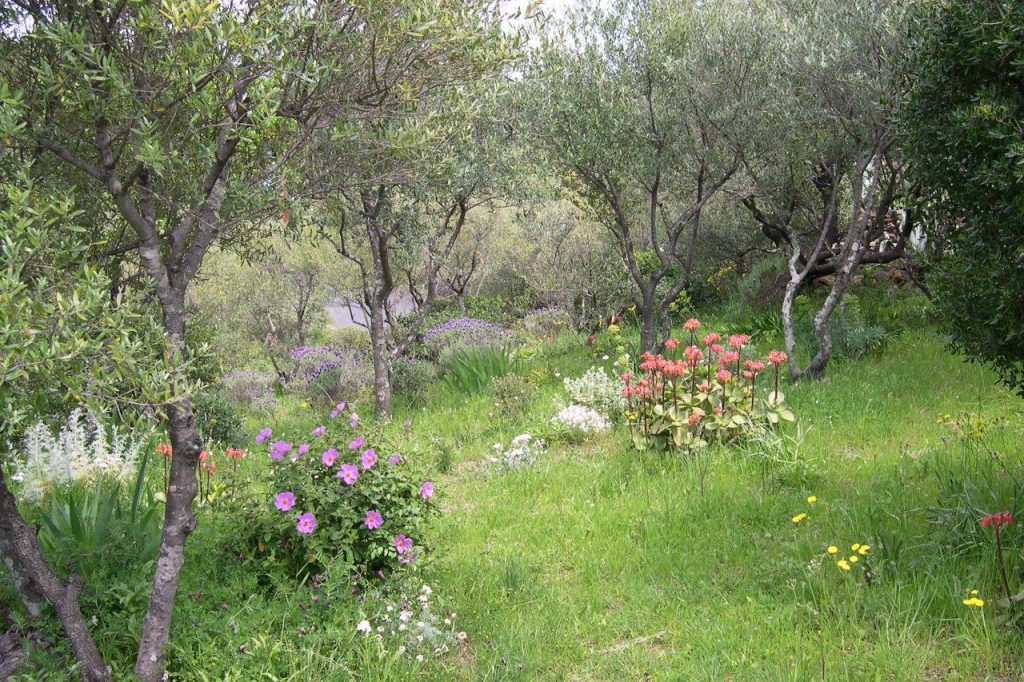

The final third of the garden to be tackled was essentially a wild olive grove which hosted a riot of wild flowers in spring until the wheat grass smothered them, turning into a brown eyesore after the mandatory summer strimming for fire risk. It faced east, so got sun in the very early morning or late afternoon, ideal for succulents which dislike sitting all day in the baking sun.

The cactuses left by the previous owner dotted around willy-nilly in the main garden were the first to be despatched to the wild garden en masse, initially more for health and safety than aesthetic reasons since I nursed many swollen fingers embedded with fine cactus spikes which caught me unawares. But once congregated in a group surrounded by chunks of schist they looked more meaningful.

The wild garden slowly graduated towards being a dry garden with cactus, agaves, aloes and succulents in the lower half, and a Filippi-style ‘sans arrosage’ on the level above.

Bulbs went in with varying success. The undoubted winner was the brilliant Chinese-yellow, crocus-shaped Sternbergia lutea which popped up out of parched soil for autumn cheer.

The deep blue Scilla peruviana just about held its own as did the massive white leucojums, though bulbs don’t seem to multiply here as they do back in the UK. The small, pale blue, star-shaped Ipheieon uniflorum were the ones which seemed most at home and happy to spread. I still hadn’t lost old habits so daffodils went in by the sackful.

Spring isn’t spring without a splash of yellow trumpet heads. And yet and yet. They do look extremely odd beside the red flowering aloes, agaves and Cotyledon macrantha. The white narcissus are fine, but daffodils look out of place, in the wrong genre. And since they also come out beside the early flowering white daisy, Rhodanthemum hosmariense, they look completely out of season.

In the dry, unmulched garden the successes were the Bulbine frutescens, the orange variety flowering in spring and autumn, and the yellow, spring-flowering only.

The cistus in various varieties were glorious for their ten day show but I never found a match for my London cistus that flowered for a solid ten months every year. The purple bulbous-rooted Tulbaghia violacae were more constant through the summer.

The Euphorbia ceratocarpa and the ferny Euphorbia cyparissias with bright green foliage and lime green flowers thrived and expanded.

Similarly, the ‘big grass’ Ampelodesmos mauritanicus which grows one metre of foliage plus two metre-high flowers for a more elegant look than pampas grass.

Tanacetum densum, with its grey foliage, stretched itself out alongside the cineraria, as did several of the low growing teucrium. The best of these was Teucrium ackermanii which flowers purple in spring, then retains its leaves as others go into deciduous summer hibernation. The crassula family, which is vast, provided several stalwarts including the pink flowering Crassula multicava which grows in dry shade and under pines even in heavy drought.

The absolute gold medal winner was the Convolvulus cneorum, dove grey leaves and white flowers, which provided a soft contrast to the sharp edged agaves and aloes. It loathes water as I discovered, initially having disregarded advice and reduced one plant to black mould.

What I found in the dry garden was if I could hold my nerve in the first year and barely water at all, then the plants thrived. OK, there were losses but the ones that kept going were in better shape thereafter than ones which had been mollycoddled through the initial stages. Leave well alone and the fittest survive.

In amongst the cultivars in spring the wild alliums rocketed up from nowhere after the soil had been turned over for the first time, probably, ever. The purple wild sweet peas were a delight, wrapping themselves round the irises. The wild lavender and helichrysum revived every spring. The wild scabious barely broke stride at the summer strimming to continue flowering till the cold came.

Since I am somewhat obsessional about having colour all the year round – admittedly easier in some areas than others – I had a calendar of anticipation.

January to March: Purple climbing hardenbergias, yellow winter-flowering jasmine, almond trees in blossom and mimosas (in neighbours’ gardens only!), rhodanthemum daisies

Spring: White and purple osteospermum daisies, climbing white Jasmine polyandrum, roses, santolina, various bulbs, Teucrium ackermanii, Westringia fruticosa (grey leaved shrub, white flowers), Coronilla glauca (grey leaved shrub with soft orange flowers), peach, apricot and cherry trees, lavender.

Summer: Ornamental grasses, passion flowers (Passiflora caerulea, P. violacae and P. jamesonii), honeysuckle, wisteria, purple succulent lampanthrus, solanum.

Late Summer to Autumn: Plumbago, salvias, lagerstraemia.

Winter: Euryops chrysanthemoides and Cotyledon macrantha (large fleshy succulents with red aloe flowers, not frost hardy), Grevillea lanigera.

The gardening climate in coastal Roussillon at 42°N 30’, almost frost free and low in rainfall was admittedly luckier than I knew. Having since moved to the Var, a degree further north and 10 kilometres from the sea, I am facing a whole new learning curve.

Plumbago barely over-winters here, nor does the Lantana montividensis. Crassulas loathe the wetter winters as do some of the agaves.

But as Olivier Filippi always says when plants die – “it’s an opportunity.” New plants to explore. Years of happy experimentation ahead to see what thrives.

Text & Photographs by Marjorie Orr

![]()